THE CHALLENGE: How do you know whether a team has a Learning Culture? Look for the Little Red Machine.

THE IDEA:

I was on-site with a professional sports team recently, and during a film review session I saw the following exchange:

Coach: “Who’s wrong on this play?”

Player sitting in the front row: “Me, coach.”

Coach: “Yeah, that’s what I think too. So walk me through your thinking?”

It happened so fast you’d be excused for missing it, but boy did that one moment tell me a ton about this team, this coach, and the culture that has been created here.

***

When I talk to coaches and front office folks, a topic that comes up frequently is how to create a “Learning Culture.” I’ve learned over the years that this is something of a loaded phrase, and there can be a wide range of potential meanings and implications lying behind the words that are spoken aloud. For me, a Learning Culture is one where leadership has taken intentional steps to create the psychological safety required for athletes or students to look bad in practice or film. Let’s unpack that a bit.

Like all complex problems, there is no one formula to follow, no checklist to complete to set up a Learning Culture. But there is a North Star to guide our actions – Do my athletes or students believe it is safe for them to make mistakes, or not know something? – and there are many practices that will help you create the psychological safety you’re seeking in your meeting room or classroom. Here are three to get you started:

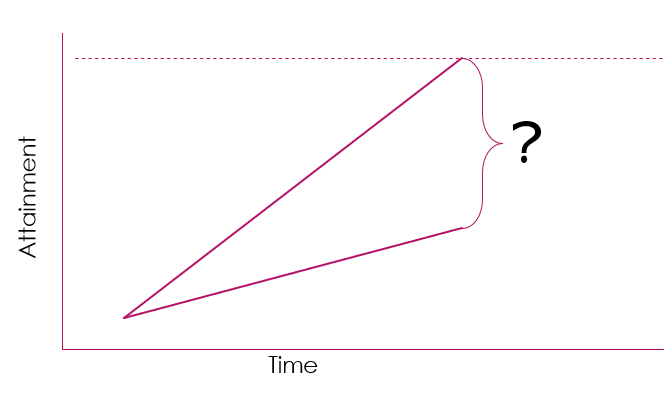

- Articulate the theory: Humans don’t learn from doing things they can currently do over and over again, they learn from stretching themselves and trying to successfully do things that are slightly harder than what they can currently do. The fancy psychology term for that second category is the Zone of Proximal Development, but “articulating the theory” doesn’t have to mean using intimidating language or technical definitions with your group. It is enough for you to tell them, “Hey, mistakes are useful around here because they tell us what we need to work on” or some similar statement that will be more accessible and relatable. We want our athletes and students to believe that they don’t need to hide their mistakes, and instead feel the freedom to stretch themselves and try hard things. And we can influence whether they feel that way by telling them we believe mistakes are not only normal, but good and important.

- Draw bright lines: Anyplace where the stakes are high, the incentives are stacked against experimentation and risk-taking; this certainly includes top-level amateur and pro sports. In a classroom setting teachers can help students know where it is safe to make mistakes (often times this includes classwork and homework) and what is evaluated (the test, the project, the final draft, etc.) In sports these lines can get blurred. When players know that their performance in practices impacts their playing time, how can we expect them to ask questions, try hard things, and be vulnerable? One WNBA coach I know draws bright lines inside of each practice so his athletes know what his expectation is. He calls it his TLC model, and his players know whether each part of practice is designed for Teaching, Learning, or Competing. During the Teaching and Learning segments players expect stoppages, are encouraged to ask clarifying questions, and offer suggestions to the coach and each other. But during the Competing portion of practice, they know he’s watching them perform and making decisions on their readiness to contribute to the team’s effort in the next game.

- Eliminate consequences for failing well: One coach I work with is fond of telling his players “I love first mistakes. I don’t love second ones.” His point is clear – mistakes are part of competition and part of learning. AND, we are trying to win, so there’s a limit to how much we can fail here. As a coach or teacher our words are powerful, and what we choose to reprimand or praise impacts the culture of our classroom, or our team. When a student or athlete tries something or says something and it’s not right, the way we make the correction determines whether that person – or anyone listening – will read your culture as a safe place for them to try hard things. Statements like “I like your thinking, but I saw it differently” or “this is hard, and I see where you went wrong” go a long way.

***

In baseball there’s a little red machine that fires ground balls at infielders during practice. When used, the resulting drill can be very challenging – the coach can make the ball travel at variable speeds ranging from fast to super-fast, with variable spin, and he/she can create different constraints for the athlete on the receiving end (e.g. using a smaller glove, or saying “ok this time field the ball to your backhand side while charging at a 45 degree angle”) that make it even harder. Because it’s hard, even elite athletes at the highest levels of baseball miss the ball some relatively high percentage of the time. And so as a result, some professionals avoid the little red machine like the plague – they don’t want it to make them look bad. Or said another way, they don’t feel like they can be vulnerable enough to make a mistake.

So the next time you are at a ballpark early, watch what the infielders are doing to get ready to play. Are they fielding routine grounders hit from a comfortable distance, at a comfortable speed, and making every catch, every throw? Or do they have that little red machine blasting them with 100MPH grounders from 20 feet away? Because while that second scenario can lead to some bruised palms and maybe even some bruised egos, that second scenario is the one where someone is getting better. Therefore its presence (or absence) tells you a ton about whether that team has established a Learning Culture.

GO DEEP:

- Doug Lemov has written a ton over the years on a similar concept he calls a “Culture of Error” – see pp 172-173 in Coach’s Guide to Teaching or Technique 12 in Teach Like a Champion 3.0

- I’ve linked to this before so that should tell you how much I like it; Eduardo Briceño’s TEDx Talk that distinguishes between “Learning Zones” and “Performance Zones” is a great way to think about how to draw those bright lines.

- If you want to have a conversation about building Learning Cultures in your classroom or on your team, you can reach out to me anytime.